|

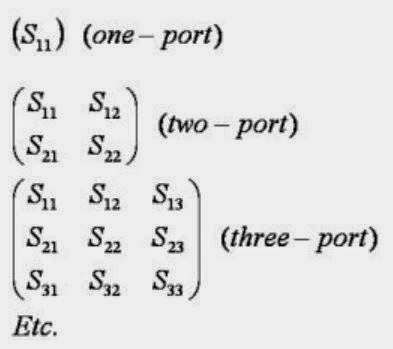

| Figure 1: S-matrices for one-, two-, and three-port RF networks |

Now, let's apply that same sort of thinking to a two-port network. When we apply a signal to the network's input, the same thing will happen as it did with the lens: Some fraction of the signal will propagate through the network but some is reflected, or scattered, back through the port it entered through. Some of the signal will be dissipated as heat, or even as electromagnetic radiation. As with the lens, we want to know what's happening with our two-port network. What is causing the scattering of the signal? Bear in mind that the “signal” is an electromagnetic wave propagating through the medium of the network, just as the light passing through the lens is also an electromagnetic wave.

The answer lies in the application of a mathematical construct called a scattering matrix (or S-matrix), which quantifies how energy propagates through a multi-port network. The S-matrix is what allows us to accurately describe the properties of incredibly complicated networks as simple "black boxes". The S-matrix for an N-port network contains N2 coefficients (S-parameters), each one representing a possible input-output path. By “multi-port network,” we could be referring to, for example, a cable or a microstrip line. How would that interface affect a 5-Gbps USB 3.0 signal? This is the sort of practical application in which S-parameters shine.

S-parameters are a “frequency-domain” description of the electrical behavior of a network. They are complex numbers, and are expressed in terms of both magnitude and phase. That's because both the magnitude and phase of the input signal are changed by the network due to losses, reflections, and propagation time. Quite often we refer to the magnitude only, because how much gain or loss occurs is typically of the most interest. However, the phase information is extremely important and should not be ignored. S-parameters are defined for a given set of frequencies and port impedance (typically 50 ohms), and vary as a function of frequency for any real-world network.

There are also mixed-mode S-parameters. Say you have a

differential lane in your circuit and you want to quantify the losses in a

differential signal. S-parameters for the differential lane can be transformed

into differential S-parameters, with which you consider differential signal

characteristics alongside of common signal characteristics.

In their most basic sense, S-parameters refer to the ratio of "voltage out versus voltage in." S-parameters come in a matrix, with the number of rows and columns equal to the number of ports. For the S-parameter subscripts "ij", j is the port that is excited (the input port), and "i" is the output port. Thus, S11 refers to the ratio of signal that reflects from port one for a signal incident on port one, as a function of frequency. S-parameters along the diagonal of the S-matrix are referred to as reflection coefficients because they only refer to what happens at a single port, while off-diagonal S-parameters are referred to as transmission coefficients, because they refer to what happens from one port to another. Figure 1 shows the S-matrices for one, two and three-port networks.

In time-domain reflectometer measurements (TDRs), a fast rising step edge is sent into the DUT and the reflected signal measured. In addition, we can look at the signal that is transmitted through the DUT. This is the time-domain transmitted signal (TDT). The signal incident into the DUT can be thought of as being composed of a series of sine waves, each with a different frequency, amplitude, and phase. Each sine wave component will interact with the DUT independently. When a sine wave reflects from the DUT, the amplitude and phase may change a different amount for each frequency. This variation gives rise to the particular reflected pattern.

Likewise, the transmitted signal will have each incident

frequency component with a different magnitude and phase. There is no

difference in the information content between the time-domain view of the TDR

or TDT signal, and the frequency-domain view. Using Fourier transform techniques,

the time-domain response can be mathematically transformed into the

frequency-domain response and back again without changing or losing any

information. While these two domains tell the same story, they emphasize

different parts of the story (Figure 2).

TDR measurements are more sensitive to the instantaneous impedance profile of the interconnect, while frequency-domain measurements are more sensitive to the total input impedance looking into the DUT. To distinguish these two domains, we also use different words to refer to them.

Time-domain measurements are TDR and TDT responses, while frequency-domain reflection and transmission responses are referred to as S (scattering) parameters. S11 is the reflected signal and S21 is the transmitted signal. They are also often termed the return loss and the insertion loss. It’s worth noting, however, that TDR and TDT typically refer to the raw measurements from the TDR instrument. From these measurements, a transform from the S-parameters yields other responses, such as impedance, step response, impulse response, single-bit responses, and more. The raw TDR and TDT measurements are typically less accurate because they are often uncalibrated (unless you’re using a Teledyne LeCroy SPARQ network analyzer; see below).

Depending on the question asked, the answer may be obtained faster from one domain or the other. If the question concerns the characteristic impedance of the uniform transmission line, the time-domain display of the information will get us the answer faster. If the question is about the bandwidth of the model, the frequency-domain display of the information will get us the answer faster. Having said that, the time-consuming TDR calibration procedure is prone to errors that can yield incorrect S-parameters. Teledyne LeCroy’s SPARQ signal-integrity network analyzers avoid this pitfall by performing automatic calibrations with an internally connected calibration kit.

In their most basic sense, S-parameters refer to the ratio of "voltage out versus voltage in." S-parameters come in a matrix, with the number of rows and columns equal to the number of ports. For the S-parameter subscripts "ij", j is the port that is excited (the input port), and "i" is the output port. Thus, S11 refers to the ratio of signal that reflects from port one for a signal incident on port one, as a function of frequency. S-parameters along the diagonal of the S-matrix are referred to as reflection coefficients because they only refer to what happens at a single port, while off-diagonal S-parameters are referred to as transmission coefficients, because they refer to what happens from one port to another. Figure 1 shows the S-matrices for one, two and three-port networks.

In time-domain reflectometer measurements (TDRs), a fast rising step edge is sent into the DUT and the reflected signal measured. In addition, we can look at the signal that is transmitted through the DUT. This is the time-domain transmitted signal (TDT). The signal incident into the DUT can be thought of as being composed of a series of sine waves, each with a different frequency, amplitude, and phase. Each sine wave component will interact with the DUT independently. When a sine wave reflects from the DUT, the amplitude and phase may change a different amount for each frequency. This variation gives rise to the particular reflected pattern.

|

| Figure 2: There are time-domain measurements and there are S-parameters; each emphasize different aspects of a transmission line's characteristics |

TDR measurements are more sensitive to the instantaneous impedance profile of the interconnect, while frequency-domain measurements are more sensitive to the total input impedance looking into the DUT. To distinguish these two domains, we also use different words to refer to them.

Time-domain measurements are TDR and TDT responses, while frequency-domain reflection and transmission responses are referred to as S (scattering) parameters. S11 is the reflected signal and S21 is the transmitted signal. They are also often termed the return loss and the insertion loss. It’s worth noting, however, that TDR and TDT typically refer to the raw measurements from the TDR instrument. From these measurements, a transform from the S-parameters yields other responses, such as impedance, step response, impulse response, single-bit responses, and more. The raw TDR and TDT measurements are typically less accurate because they are often uncalibrated (unless you’re using a Teledyne LeCroy SPARQ network analyzer; see below).

Depending on the question asked, the answer may be obtained faster from one domain or the other. If the question concerns the characteristic impedance of the uniform transmission line, the time-domain display of the information will get us the answer faster. If the question is about the bandwidth of the model, the frequency-domain display of the information will get us the answer faster. Having said that, the time-consuming TDR calibration procedure is prone to errors that can yield incorrect S-parameters. Teledyne LeCroy’s SPARQ signal-integrity network analyzers avoid this pitfall by performing automatic calibrations with an internally connected calibration kit.

No comments:

Post a Comment